By Ann Pettifor – posted March 25th on Labour List

There is a ferocious battle being played out around how we should interpret and understand the financial crisis and its consequences. And I am not talking about the crude and quite hysterical response to the budget in the Conservative press today. That we can safely ignore. No, it’s more than that. It’s about key economic issues, and it’s vital that we all grasp them, and fight the good fight on behalf of those who will be victims of orthodox economic ideology.

The orthodox story line goes like this: the most momentous crisis facing the world is government debt – not economic failure and collapse; not the collapse of private investment; not financial instability, or deflation, or currency volatility or the threat of a dangerous rise in protectionism and a new global trade war. And certainly not the rise in unemployment.

No: the biggest threat facing civilisation is the rise in government debt.

Why? Because the rise in government debt ‘crowds out’ private debt. In other words, creditors (bankers and other lenders) can’t sell credit/loans at high prices (or rates of interest) if governments are in the markets selling/offering debt at lower rates of interest. So government debt must be cut. The public sector must be shrunk.

Today’s Financial Times spells out very clearly these lines of debate – and where the FT and its supporters in the Tory Party and City of London stand.

Martin Wolf, a highly respected FT commentator writes thus: “Since the economy is substantially smaller than expected, the size of the state has to follow. The question is how and when.”

That’s it. No questions asked. The logic, it appears, is unassailable. The size of the state has to shrink.

Precisely the same logic was applied during the crisis of the 1930s. And it was followed, to disastrous effect between 1929 and 1933. The consequences were what we are witnessing today: deflation; economic failure; currency volatility; the rise of protectionism and trade wars; and of course a massive rise in unemployment.

It was only when President Roosevelt took the reins after 4 years of such economic logic (in 1933) that the US economy turned around. And it was only when J M Keynes took the reins at the Bank of England and the Treasury (in 1933) that the UK economy started to turn around – and government debt started to fall.

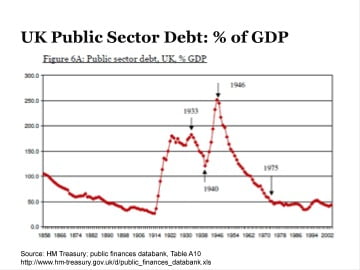

I point you once again to my favoured chart from the Treasury. It’s one that should be pasted on the wall of every single Labour Party candidate’s election HQ.

Keynes (and Roosevelt) had proposed a different logic. To paraphrase: “Since the economy is substantially smaller than expected, government must take action to re-boot the economy, and to stimulate economic activity – in both the public and private spheres.”

“By re-booting the economy, government can expect to generate government revenues – to pay for the re-booting.” Of course they had never heard of the term re-booting, but that pretty much is what they argued, and what they went on to do.

And it worked.

Look at the chart at see what happens to government debt between 1933 and the start of the war in 1939. It falls, quite precipitously. That’s because economic activity generates tax revenues. Government spending pays for itself.

Yesterday, the Chancellor was right to boast about the £11 billion fall in government borrowing. A direct result of the mini fiscal stimulus of last year. The improvement has come from tax receipts and the stimulus measures adopted, including the cut in VAT. Regrettably it has not come from employment taxes. This demonstrates, nevertheless, that taxes are key to correcting the deficit, and that stimulus works in reducing the deficit.

The remainder of the £11bn improvement has come from lower-than-anticipated gilt yields. In other words, the government paid less for its debt on the international markets, than many, including FT writers had predicted. So much for: “cuts are needed to reassure financial markets and persuade them to lend to the government at lower rates of interest”.

With those numbers Darling has seen off the deficit hawks in the Tory Party, the Institute of Fiscal Studies, the City and the BBC.

He has been proved right: a little fiscal stimulus staved off even higher unemployment and bankruptcies and helped stabilise the economy.

Above all, he has proved, unequivocally, that government spending pays for itself.

Today John Authers of the Financial Times interprets this fall in borrowing in this way: “the government’s borrowing needs are somewhat lower than had been expected by the market (at £163 bn against expectations of about £185 bn) thanks to spending cuts. (My italics).

This is contradictory: on the one hand the FT complains that spending cuts are inadequate. On the other it argues that the fall in government borrowing is precisely due to spending cuts!

Spending cuts vs stimulus. The FT and the Tories are winning this argument, and the consequences for the Labour movement are dire. Because private sector investment continues to fall; because £46 billion was taken out of the economy last year; and because government is being brow-beaten into contributing to further falls in economic activity (by cutting spending) we can look forward to : rising unemployment, falling wages, rocketing bankruptcies and deflation (which increases the cost of debt).

This will lead to a loss of confidence in democratic institutions, to votes for those that promise to deal with the crisis by authoritarian means, and to social unrest.

Regrettably, instead of using the better borrowing numbers, as proof, and as a springboard for an even greater stimulus, the Chancellor yesterday began the process of fiercely turning down the public spending screw. The numbers of those in full-time employment will continue to fall, and so will real wages.

So, there is a great deal at stake in this ideological debate. Labour Party members must get stuck in.

Not only Labour Party members but also LibDem Party members. Though I understand your allegiance here. I am mentioning the LibDems because I think the more criticism we can get of the Tories, the better.

We should expect the rich to espouse the positions they do. In Roosevelt’s time, the response by some of the rich was potentially more destabilizing than that of the rich today. But perhaps the rich of today feel more secure, politically and financially, than their counterparts did in the mid-’30s.

While I do hope that the rich would see their interests in a broader and more sustainable light, it is probably fantasy on my part to even minimally expect that to be possible. Therefore, for the rich to take anyone other than themselves into account, they must be made an offer they feel unable to reject. The rich of today contribute less of substance than did the rich of the 19th century. Hence, there is more reason than ever to reject their self-serving apologetics.

I have looked at the Excel document and was unable to locate the displayed chart. Could it have been removed? I realize it ought to be there, according to the chart caption itself, but I looked at pages A1 through C4 and did not see it.

Larry, am on the case…sorry for the delay in responding, been having trouble as a result of ‘upgrading’ broadband with BT…..have also had trouble today finding this database….will get back to you. Hope the Treasury has not taken it down!

Dear Ann

I have just commented on the Labour List, whereas here something went wrong. So I’m trying again: would you please have a look at my analysis of the UK budget over the last 10 years and see whether you come to similar conclusions as I do?

It’s rather incredible how the crisis hits the statistics. See http://bit.ly/aYhEnT

With best wishes for becoming an MP,

Sabine

Organiser, Forum for Stable Currencies

http://forumforstablecurrencies.info

Interesting – but I cannot understand some of the arguments you forward. It would seem to me that the post war years are fundamentally different from the situation we have today. For one, the level of personal indebtedness are magnitudes of order higher. Further we needed to rebuild after the war and the rebuilding was in productive assets (I assume).

Also, unless I have got the wrong end of the stick (something I am always prepared to admit), the drop in forecast debt was simply that…. that we failed to be as indebted as expected. Cynically, it could be argued that a high forecast was given in order to have something positive to say in the budget. It seems to me that a message of ‘things are not as bad as we forecast’ is hardly good news or a measure of the fiscal responsibility of government.

Your ideology is clear – more debt to solve the problem of more debt. Read “This Time it is Different” and tell me exactly how a sovereign debt crisis can be avoided by taking on more sovereign debt, and what examples you have from history that high levels lead to prosperity.

I look forward to your thoughts.

Simon, thank you for this, but you get me wrong. I am not ideological about debt. However, I am clear that government debt is a very different animal from personal or household debt. Government spending – on as you say ‘productive assets’ – generates income. This is in stark contrast to private investment, in say home insulation. A householder may invest in insulation, and make savings in the future, but would not obtain income from the person employed to build the insulation. The government however, is paid taxes by the persons subsidised to insulate homes and other productive activity….and then pays VAT in the shops, which helps shopkeepers make a profit, and they then pay taxes on that…..

So government investment (as shown after the second world war) stimulates economic activity, economic recovery, which in turn helps pay down the debt. That is not ideological. It is a matter of fact. However, government investment in say bailing out bankers – may not generate income for government. That is an important distinction, as you say.